Pakistan’s Giant Leap: Astronauts to Train in China

April 26, 2025

USF’s Digital Revolution Aims To Empower Women Through Tech

April 26, 2025Pakistan Needs A Private-Sector R&D Revolution

Pakistan’s IT industry has yet to emerge as a significant innovator on the global stage. Despite a large population and a growing pool of IT graduates, the country has produced few internationally recognized tech products or companies. The local market relies heavily on imported software and services while the absence of homegrown tech giants or breakthrough products highlights a limited innovation capacity in the domestic IT sector.

Although local startups have attracted investment in recent years, their scale remains modest. For example, all Pakistani tech startups combined raised under $30 million in venture funding in 2018, whereas startups in Indonesia raised nine times more in the same year [1]. The collapse of what would have been Pakistan’s first unicorn (the rapid-delivery startup Airlift) in 2022 underscored the fragility of the ecosystem [2]. In short, Pakistan’s tech industry, while growing in numbers, has yet to produce the kind of innovative output seen in peer countries – this glaring gap in R&D effort underscores an uncomfortable reality: Pakistan is under-investing in its future.

R&D in Pakistan: Low Funding and Weak Linkages

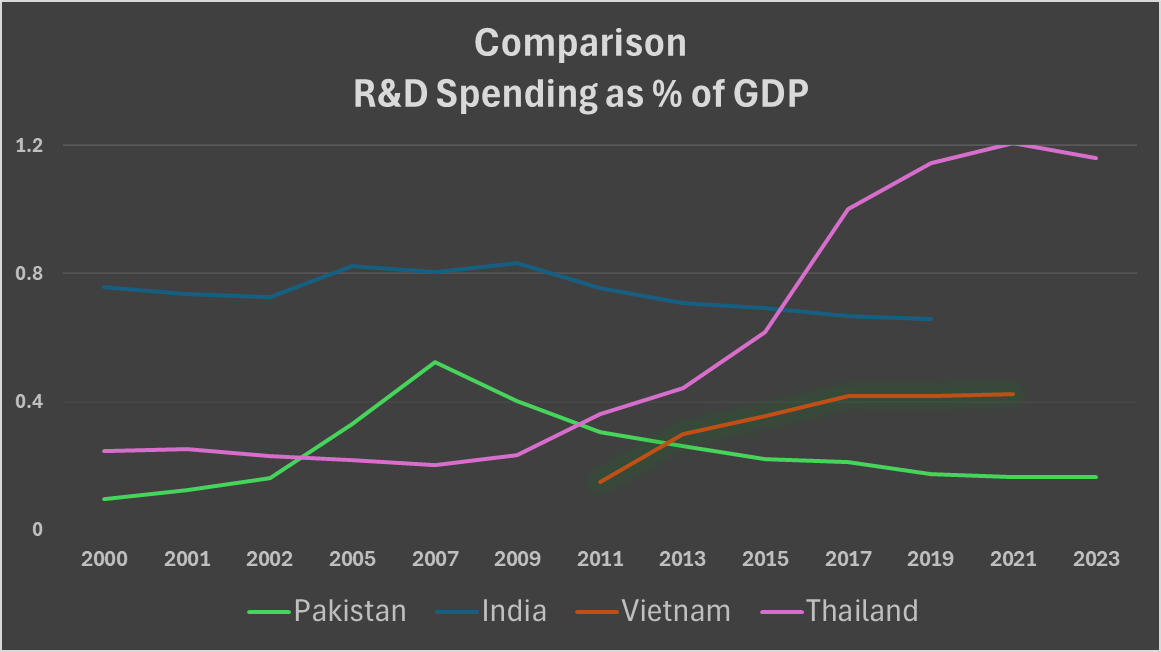

One of the key factors behind this innovation deficit is Pakistan’s underdeveloped R&D landscape. National spending on R&D is among the lowest in the region, averaging a mere 0.3–0.4% of GDP in the past decade [3]. For context, India spends about 0.7% of GDP on R&D, Thailand 0.4%, and innovation-driven economies like Singapore over 2% [3]. According to the World Bank, Pakistan’s R&D outlay was just 0.16% of GDP in 2023, effectively stagnating or declining in recent years [4].

![[Source : data.worldbank.org]](https://digitalpakistan.pk/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/1-1.png)

[Source : data.worldbank.org]

Figure: R&D expenditure as percentage of GDP for Pakistan and peers (2000–2023). Pakistan’s spending (green) remains far below that of innovation leaders like Vietnam (orange) and even other developing countries such as India (blue) and Thailand (purple) ( unesco.org).

The limited funding that does exist comes predominantly from the public sector (through bodies like the HEC and the Ignite), with negligible contribution from private industry. Universities and government research centers conduct most of the formal R&D, but often in isolation from commercial needs. There are “limited formal knowledge transfer mechanisms”, and gaps in collaboration between educational institutions and businesses “restrict innovation” [5]. The result is that Pakistan’s R&D ecosystem operates in silos: a small public R&D effort not linked to industry, and an industry with limited investment in R&D.

Pakistan ranked 91st of 133 countries in the 2024 Global Innovation Index (www.wipo.int), reflecting that it performs poorly on innovation inputs (such as R&D investment, human capital, and infrastructure). The country fares slightly better on innovation outputs (like startup creation) than its inputs rank, suggesting that the talent and ideas exist, but they are not being adequately supported by investment. Indeed, analysts note “Pakistan has shown a baffling lack of interest in R&D spending over the years.”.

Let’s see the innovation journeys of a few countries from developed and the developing world as a comparison.

United States:

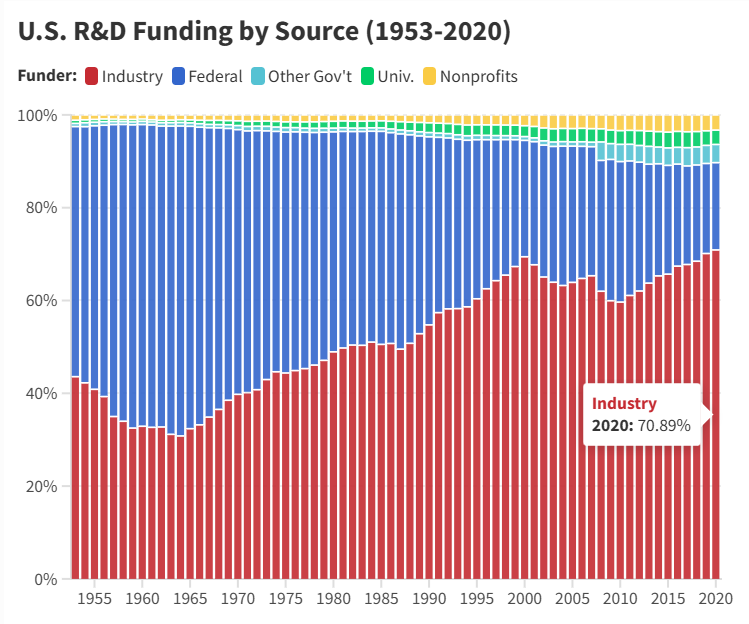

Countries like the U.S. demonstrate how robust private-sector R&D drives innovation. The U.S. leads in technology innovation largely because its private companies invest heavily in R&D and an extensive venture capital (VC) system fuels new ideas. Ten largest U.S. tech firms together poured roughly $222 billion into R&D in 2022, with Amazon alone investing over $73 billion [6]. To put that in perspective, one single U.S. company (Amazon) spent more on R&D last year than Pakistan’s entire GDP percentage spend on R&D for the past decade. This massive private R&D commitment (about 2.5% of U.S. GDP [7]) far eclipses what most governments spend, creating a continuous pipeline of innovation. Unlike popular opinion that most R&D funding in US comes from the public sector, private sector contribution in R&D stands at impressive >70 % as of 2020 according to survey by National Science Foundation indicating that innovation is primarily driven by private sector especially after the internet boom.

US R&D Funding by Source

Taiwan:

Taiwan is a global leader in semiconductor technology – home to TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.), the world’s most advanced chipmaker – thanks to a deliberate strategy of public-private collaboration in R&D. In the 1970s, recognizing it lacked natural resources, Taiwan’s government decided to invest in technological capability. It established the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) in 1973 as a state-backed R&D hub to nurture high-tech industry [8]. ITRI acted as an incubator and open laboratory where researchers worked closely with companies, effectively transferring knowledge to the nascent private tech sector. This model bore fruit: ITRI’s labs fostered the creation of companies like United Microelectronics Corp. (UMC) and TSMC, now giants in the chip industry [9]. Through the 1980s and 1990s, Taiwan’s government and industry co-invested in developing semiconductor know-how, often licensing technology from abroad and improving on it domestically.

TSMC, though a private company, invests heavily in research to stay ahead. TSMC spent around US$5.5 billion on R&D in 2022 (about 7% of its revenue) [10]. Many of Taiwan’s tech innovations – from high-end chips to electronics manufacturing processes – stem from industrial R&D partnerships linking firms with institutes like ITRI and academic labs.

India:

India’s trajectory, in some ways, runs parallel to Pakistan’s in the early stages – both started as predominantly IT service-oriented economies – but India has rapidly evolved its innovation ecosystem by increasing private sector involvement in R&D. Historically, India’s R&D expenditure was dominated by the government (through agencies like CSIR and DRDO) and hovered around 0.6–0.7% of GDP [11]. In recent years, however, the private sector’s share in R&D has been rising, fueled by both large tech firms and a booming startup scene. India’s IT services giants (TCS, Infosys, Wipro, etc.), which once focused only on outsourcing, have started investing in proprietary platforms and products – especially in emerging areas like artificial intelligence and automation. For example, TCS created a dedicated business unit (Digitate) for its AI-driven automation platform “Ignio,” and Wipro developed its own AI platform “Holmes,” as part of a push to develop intellectual property [12]. Similarly, Infosys launched its AI platform “Nia” (building on an earlier tool called Mana) to offer AI solutions to clients [12].

Importantly, India has cultivated a vibrant startup and venture capital ecosystem in the last decade, which has significantly boosted private R&D and innovation. As of 2023, India is home to around 70 unicorns (billion-dollar startups) [13], reflecting the explosion of tech entrepreneurship there.

South Korea:

South Korea stands as a prime example of a country that transformed into a tech innovation leader through aggressive private R&D investment coupled with strategic government support. In the 1960s and ’70s, Korean government identified technology as the key to growth and forged close partnerships with a handful of conglomerates (chaebols) to drive industrial R&D. Today, South Korea spends over 4.5% of its GDP on R&D (5.21% in 2022 [14], one of the highest in the world), and the private sector accounts for roughly 76% of that spending [15]. Korean corporations like Samsung, LG, and Hyundai have built extensive R&D operations that consistently push the technological frontier in their fields (smartphones, semiconductors, consumer electronics, automobiles, etc.). For instance, Samsung Electronics spent about ₩21.2 trillion (US$15.4 billion) on R&D in 2021, an amount nearly equal to the R&D spending of the entire Korean government that year [16]. Korea consistently ranks among the top in global innovation indices, patents per capita, and high-tech exports.

Why Pakistan’s Private Sector Lags in R&D

If private sector driven R&D is so crucial to innovation, why has Pakistan’s private sector been largely missing from the equation? Several interrelated factors have kept Pakistani companies on the sidelines of research and innovation:

- Lack of Incentives and Policy Support: Pakistan’s business environment historically has not rewarded R&D investment. There have been few tax incentives, grants, or policy programs to encourage companies to spend on research or new product development. Unlike countries that offer R&D tax credits or subsidized innovation programs, Pakistan gives its firms little cushion to take on the cost and risk of R&D. This absence of support contributes to what economists call a market failure – companies under-invest in R&D because they cannot capture all the benefits and the state hasn’t intervened enough to correct this [3]. In essence, many firms view innovation as “someone else’s job”, expecting the government or universities to handle research.

- Weak Intellectual Property (IP) Protection: A major deterrent to private R&D is the concern that even if a firm invents something novel, it may not be able to fully reap the rewards due to piracy or weak enforcement of IP rights. Unfortunately, Pakistan struggles with widespread counterfeiting and IP infringement, which “poses a risk to innovation and economic development” [17]. Although Pakistan has modern IP laws on paper, enforcement is patchy – legal processes for patent or copyright disputes are slow and cumbersome, often discouraging companies from even filing for protection [17]. The result is a preference for low-risk, easily defensible business models (like services or trading) over original tech development.

- Risk Aversion and Short-Term Business Mindset: Many Pakistani businesses are family-owned and tend to be conservative in their approach. R&D is inherently risky – it requires spending money on experiments and projects that might fail or pay off only in the long run. In Pakistan, business owners often see R&D as an avoidable cost rather than a strategic investment. Moreover, limited competition in certain domestic markets has allowed companies to prosper without innovating, reinforcing complacency.

- Absence of a Corporate R&D Culture: Because few Pakistani firms historically engaged in R&D, there is a self-perpetuating lack of an innovation culture. Companies do not have dedicated R&D units or labs, and rarely allocate budgets for experimentation. There are also few role models or success stories of Pakistani firms that innovated and saw big payoffs – which makes it harder to inspire other business leaders to follow suit. In Silicon Valley or Bangalore, engineers can point to success stories and say “let’s do likewise,” but in Pakistan the narrative is missing. Many companies also lack technical personnel with PhDs or research training; the hiring focus is on operational roles, not researchers, due to the limited demand for R&D internally. All of this creates a vicious cycle: because previous generations of businesses didn’t prioritize R&D, today’s businesses have no established R&D processes or talent, and thus they themselves don’t embark on research initiatives. It’s a cultural gap as much as an economic one – innovation hasn’t been part of the DNA of most Pakistani enterprises. Changing this mindset is challenging, especially in family-run firms where tradition often outweighs experimentation.

Pakistan’s private sector has been held back in innovation by a combination of policy shortcomings (few incentives, weak IP enforcement) and cultural inertia (risk aversion and no tradition of R&D). Corporations logically ask: “Why invest in expensive research that might not pay off, especially if any new ideas could be copied or if we’re doing fine without innovating?”.

Where to go from here?

The public sector alone cannot deliver the level of innovation needed; Pakistan’s IT industry itself needs to invest in its own future. There are many steps that are needed and we can only list a few here.

- Introduce R&D Tax Incentives: The government may offer meaningful tax credits or deductions for R&D expenditures by companies. For example, if a tech firm invests in a new software research project or product development paired with enhanced allowances for hiring researchers or purchasing R&D equipment, a substantial portion of that cost could be deducted from taxable income. Such incentives are common in many countries and help reduce the effective cost of R&D for firms. This policy could be. The goal is to provides a short-term financial benefit via tax savings – nudging companies to think longer-term.

- Public-Private Co-Funding Programs: The state can co-invest with industry in research initiatives. This could take the form of matching grants – for instance, if a software company sets up an R&D project on Agentic applications, the government’s innovation fund (HEC, Ignite, or a dedicated R&D authority) could match every rupee the company spends, effectively halving the cost for the firm. Another approach is establishing public-private research centers focused on strategic tech areas (AI, cybersecurity, semiconductors, etc.), where government provides initial infrastructure and operational support while multiple companies contribute funds and researchers. These centers would serve as platforms for shared innovation, and participating firms can later commercialize the outcomes. Even guarantees against loss for investors in new tech ventures could be considered [13], so that venture capitalists and corporations feel more secure investing in high-risk, high-reward innovations.

- Engage the Pakistani Diaspora and International VCs: One of Pakistan’s most underutilized assets is its large diaspora of skilled professionals and entrepreneurs, many of whom have succeeded in global tech hubs. Bridging local innovation efforts with this diaspora can bring both capital and expertise. Policies to make it easier for overseas Pakistanis to invest (streamlining regulatory approvals, improving forex repatriation rules, etc.) will help. Pakistan might also explore setting up a fund of funds that co-invests in VC funds focusing on Pakistani tech, again sharing risk. Knowledge and capital from abroad can significantly accelerate domestic innovation if actively courted.

- Strengthening Industry-Academia Partnerships: Breaking the silos between academic research and industry practice is vital. Companies could “adopt” university labs, funding specific research projects in areas of mutual interest (e.g., a cybersecurity company funding a university’s cryptography lab). In return, the company gets early access to relevant innovations and talent. Government can facilitate these linkages by offering grants that require an industry partner and an academic partner together (ensuring neither works in isolation. Many existing collaborations between universities and industries are ad-hoc, lacking formal structures that define roles, expectations, and outcomes. There is a need to not only structure the engagement but to also invest in infrastructure and training programs necessary for collaborative R&D.

- Build Corporate R&D Labs and Innovation Teams: Pakistani companies – especially the larger enterprises – need to start establishing dedicated R&D or “innovation” departments. Many corporate R&D initiatives in Pakistan lack a long-term strategic vision. Instead of focusing on groundbreaking innovations, these labs often concentrate on incremental improvements or immediate operational needs. This is as much a mindset shift as an organizational one. Corporate leadership should allocate a small percentage of revenue (even 1-2% to start with) towards exploratory projects, prototyping new products, or process innovations. If a few leading firms demonstrate success (say, an R&D effort leading to a profitable product line or significant cost savings), it will encourage others to follow suit.

Conclusion

Pakistan stands at a crossroads in its technology journey. The country has an educated young population, growing digital infrastructure, and no shortage of entrepreneurial ambition – the ingredients for an innovation economy are there. What’s missing is the spark of substantial private sector investment in R&D backed by public sector support and patronage. In the long run, an innovation-driven IT industry can be the engine of economic growth that Pakistan sorely needs, reducing reliance on traditional sectors and making the economy more resilient.

About the Writer:

Dr. Usman Zia is Director Technology at InnoVista and Associate Professor at the School of Interdisciplinary Engineering and Sciences (SINES), National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST), Pakistan. His research interests are Large Language Models, Natural Language Processing, Deep Learning and Machine Learning. He has authored numerous publications on language generation and machine learning. As an AI enthusiast, he is actively involved in several projects related to generative AI and LLMs.