To English or not to English, that is the question

December 22, 2022

It’s time we put the ethics back in tech.

December 22, 2022Ban. Unban. Repeat. The Censorship Ping Pong Debacle

Written by: Hamail Habib

An overview of the ping pong of decisions

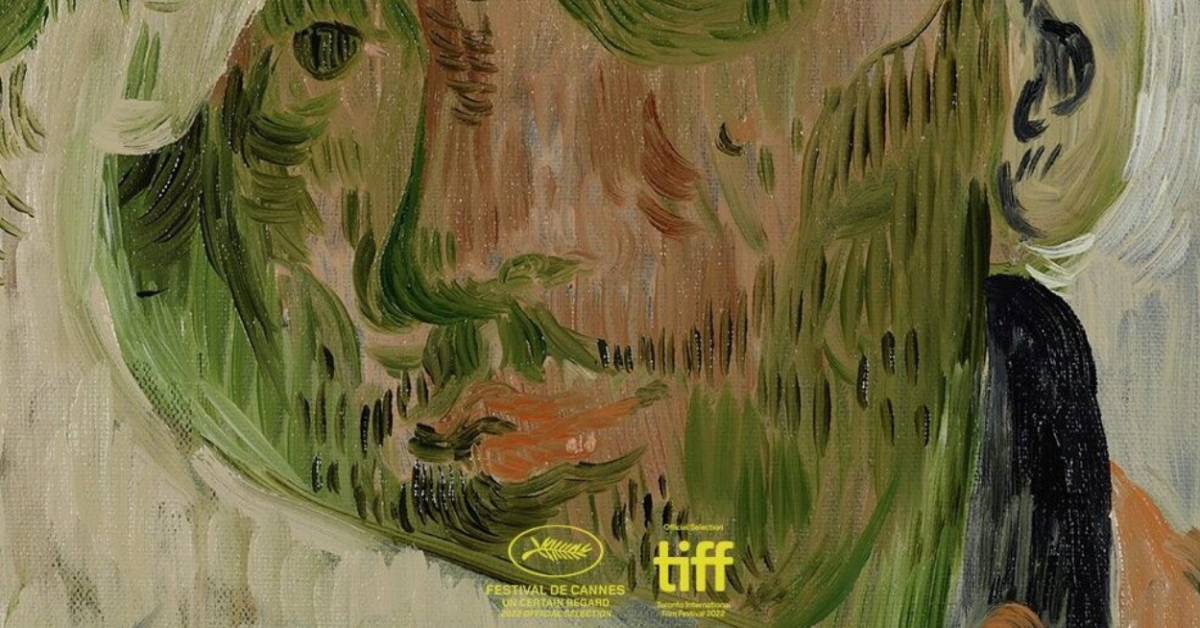

Previously given the green light by all three censor boards in Pakistan via a clearance certificate on the 17th of August, Joyland was all set to screen on November 18th across Pakistan.

This was only until the film was declared uncertified by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting on the November 11. Mobashir Hasan (PIO – Principal Information Officer) announced the decertification but he did not, however, elaborate on the ‘why’ of the decision, concluding only that doing so was legally justifiable under a 1979 order.

Following backlash on social media and elsewhere from celebrities and potential viewers alike, Salman Sufi (the Head of the PM’s Strategic Reforms) tweeted on Monday, November 14th, referring to the formation of a high-level committee under the PM’s instructions to “assess the complaints as well as merits to decide on its release in Pakistan.” The film then witnessed a miraculous reversal of the ban imposed on it.

But this sliver of light too shone only until it could, for in less than the next 24 hours, on Monday, November 17th, Sarmad Khoosat (producer of Joyland) received a notice from the government of Punjab’s Punjab Information and Culture Department, stating unequivocally that the film could not be exhibited in the jurisdiction of the Punjab Province.

Declining Authority leaving the Censor Board at loss?

“We–as a team–are gutted by this development. I am compelled to say that this sudden U-turn of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting is absolutely unconstitutional and illegal.”

– Director Saim Sadiq

The political nature of the Censor Board in Pakistan runs at odds with the status of Pakistan as a democracy, for in a democracy, censorship and the Censor Board must be apolitical. The very first instance of political intervention was indeed the bowing to pressure from far-right religious conservatives, whereby the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting conveniently stepped beyond its authority, and banned an already certified film. For what else is political intervention, but the presence of representatives from ISI and ISPR, intelligence officers that is, in a discourse on art. Together, the very existence of the ban and unban does but one thing, question the credibility of a decision by the Censor Boards, just as it questions the very glue that should bind the government and such institutions together, for all we see is a tug of war, or tic-tac-toe, where there is anything by unity among the institutions.

Joyland, the Political Opportunity.

In a matter of days, Pakistan and the world witnessed Joyland metamorphosize from an artistic expression to a political opportunity, all fresh and ready to be cashed so as to woo and bag as much support as possible.

Farwa Naqvi (a journalist and psychotherapist) saw the calls for a ban as a political ploy by religious parties to gain support for the upcoming elections; for the JI, Senator Mushtaq Ahmed Khan admitted to not having seen the film but basing his opinion and opposition on information from “authentic sources” about its content and plot. Thus, one might see this as a testimony to their having no concern for the film’s credibility or worth, but only a pursuit of a shortcut to unwavering support from the like-minded masses.

A Filmmaker’s Dilemma, and in his eyes, that of the Audience

When featured on the show Aaj Shahzeb Khanzada Kay Saath, Sadiq mentioned how there are misconceptions as to a film’s role, that it is, in reality, not to promote but merely depict.

In her conversation with Dawn, artist and designer Misha Japanwala talked about the constant fear there is for younger artists, where “if a select few men in power don’t agree with the art we’re creating, we need to think twice about making it.”

Method Actor Ahmed Majeed, also in conversation with Dawn, reported, “We don’t have a set identity; both as a country or in terms of art — I think rather than thinking about ‘preserving’ we should be more active in finding out what our identity is instead of trying to shine too bright too soon.”

Such a ping pong of decisions thus takes away the audience’s agency to choose, and decide, upon the worth of art. While there is a matter of whether the Pakistani viewership is yet as intellectually mature enough to question and analyze art, the banning of films is nonetheless questionable considering these are entertainment opportunities that people have the option to opt-out of.

For a filmmaker, it takes away his security, and, consequently, his honesty, integrity, and confidence, which he must pour into his work. For you may never know where the next criticism might strike from, or when, since even when the troubled waters seem to calm, there is no guarantee a storm isn’t raging ahead.

Hamail Habib

Student of Mass Communication at NUST Islamabad, Trainee at Jazz (Digital Pakistan Fellow)

An aspiring poet and writer, I created my first poem at the age of three, and have always been driven by the power of words that makes them mean much more than the sum of their parts.

I enjoy both creative and technical writing, and my areas of interest include lifestyle, ethics and emotional intelligence, mental health, and analyzing social issues and current affairs, to name a few.

You can find me at [email protected]