The fate of Twitter is in the hands of a business tycoon. Will it work out?

December 5, 2022

WhatsApp has become all the more favourite among users of all ages with these interesting new features; including texting yourself.

December 14, 2022You can’t look away from a train wreck – which means that people like to watch things happen. It is human nature to gawk at interesting things and a camera allows for these things to reach a greater audience. Such is the job of a photojournalist; to gawk and shoot. Most would believe that the job ends here but that’s not always the case. Photojournalism comes with a number of dilemmas and responsibilities, all of them testing the practitioner’s ethical and moral standings. The most difficult question of these being when to use the camera and when to set it aside.

A lot of times photojournalists come off as insensitive and avaricious for shooting at a sensitive time or more commonly, at times when they could’ve provided valuable help. There have been a number of such instances of severe criticism on photojournalists in the past.

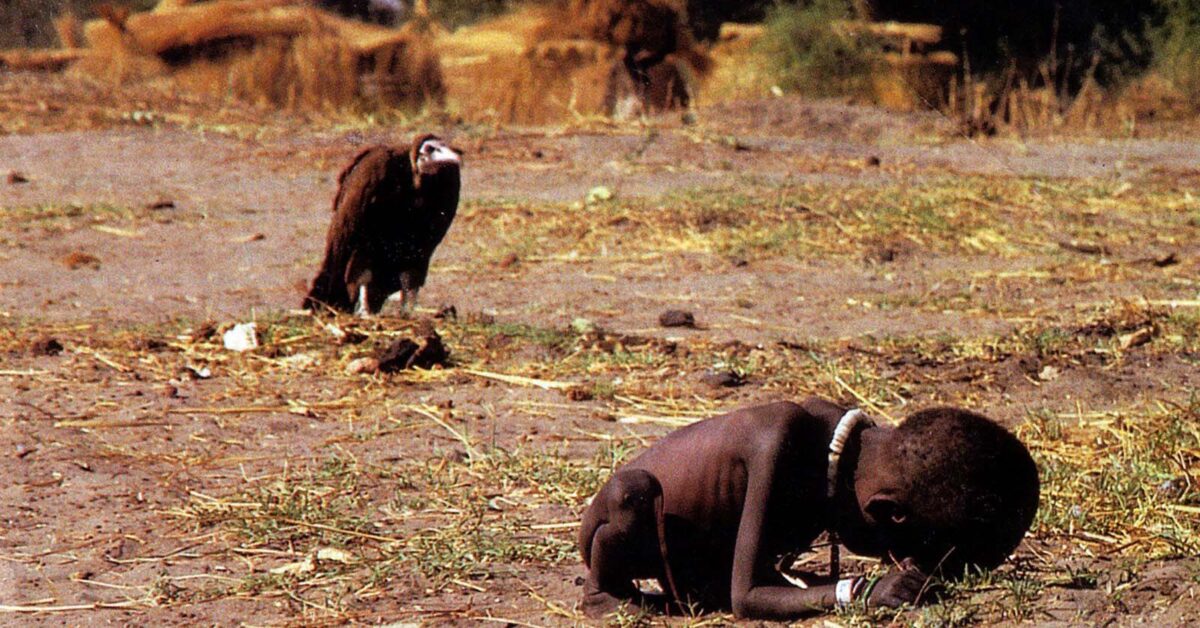

The Vulture and the Little Girl – Kevin Carter

The Vulture and the Little Girl, photographed by Kevin Carter and published in the New York Times on March 26, 1993 shows the suffering of a child during the Sudanese Famine by showing a frail little boy, originally mistaken for a girl, who had collapsed and was being eyed by a hooded vulture nearby. It is one of the most confrontational photographs ever taken, but also the most influential. The readers’ reaction towards it was intense and not all positive. Many questioned Carter on why he didn’t leave the camera and run to the child’s help, pinning him as inhumane and insensitive.

Ironically, this picture received The Pulitzer Award in 1994 which only added to the already aggressive criticism. By the end of July 1994, Carter committed suicide. This event showed that he was not at all emotionally detached and the horrors he had seen had affected him and fatally so. The criticism he received only added to his guilt and he continued to question his integrity until he couldn’t anymore. This and many such stories show the ethical complexity this profession holds. But why was he given the Pulitzer Award?

Carter’s photograph, however horrendous as it may seem, brought attention to the problem in Sudan. So much so that it implored the UN to take further action for the cause. It was used in papers and magazines around the world and ultimately played a major role in curbing the famine. Had Carter chosen to help the boy instead of taking the picture in that moment, a large number of funds that were sent by people after receiving stimulation from the picture, never would’ve reached Sudan. Carter would’ve managed to help one person in that moment, but it would’ve been at the cost of thousands more, simply because he chose to do what he thought was best instead of doing his job. This is what it means to be a photojournalist; to weigh the aid you can provide by abandoning your job and getting involved or by remaining invisible and being the eyes of people, and to make that decision timely.

You can’t look away from a train wreck, but should the train wreck always be recorded?

The photojournalist’s role is to gather stories and unlike journalists who only tell these stories, a photojournalist allows people to visualize them, greatly adding to the emotional appeal. Even after taking a controversial picture, the practitioner has the option to publish it or not, but if the photograph is never taken, that decision will never be made.

Which concludes that despite a considerably large number of ethical dilemmas regarding the process and requirements of photojournalism, the fact of the matter remains that this field requires a certain level of emotional detachment from its practitioners. It is a war they have to fight at all times against themselves in order to stay true to their jobs; a job that is equally as important as any other form of journalism. If the journalist never takes the picture, the story will never be forwarded to the world and many voices would die out in the noise.